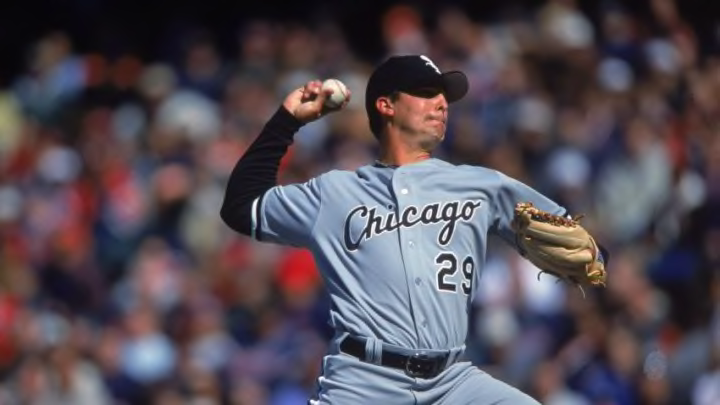

Mount Rushmore of White Sox closers: Bobby Jenks

Another pitcher drafted by the Angels and tried as a starter, Bobby Jenks — like Roberto Hernandez — followed the road from Orange County to Chicago and stardom. He was a fifth-round pick by the then-Anaheim Angels from Inglenoor High School in Kenmore, Washington.

An elbow injury sidelined him for most of the 2004 season in the minors and Jenks was designated for assignment, with the Chicago White Sox claiming him off waivers in December 2004.

The White Sox converted the 6-foot-4, 275-pound right-hander to a closer at Double-A Birmingham, where he saved 19 games before getting the call to the bigs in July 2005.

He spent much of the next 2½ months setting things up for closer Dustin Hermanson, but when the veteran injured his back in September, Jenks was thrown into the void as the closer.

He saved two games in Chicago’s ALDS sweep of the defending World Champion Boston Red Sox and two more in their sweep of the Houston Astros to win their first title in 88 years.

Jenks was an All-Star in both 2006 and 2007, topping the 40-save mark each season. He was particularly dominant in 2007, with a 0.892 WHIP while pitching more to contact and less for strikeouts.

But his number started to slip and in December 2010, he was non-tendered by the White Sox. He signed the the Red Sox, but never regained his old form because of back problems and did not pitch in the majors after the 2011 season.

In six years for the White Sox, Jenks had a 3.40 ERA and 1.206 WHIP in 341.2 innings over 282 appearances, with 173 saves in 199 chances. Jenks fanned 8.8 batters per nine innings while walking 2.9 per nine.